- Home

- L. T. Meade

Turquoise and Ruby Page 5

Turquoise and Ruby Read online

Page 5

always talking inthat fashion--always demanding things she could not possibly get--alwayshoping against hope that her beauty would win her a good match in thematrimonial market. But now Penelope thought over the letter with verydifferent feelings. If she could, by any possibility, gratify Brenda,she thought that happiness might not be unknown to her. She lovedBrenda: she admired her very great beauty. She hated to see hershabbily dressed. She hated to think of her as going through insult anddisagreeable times. She felt that, if she had the ordering of theworld, she would shower riches and blessings and love and devotion onher sister, and be happy in her happiness. If ever she had goldendreams, the dreams turned in the direction of Brenda. If ever hertalents brought forth fruit, the fruit should be for Brenda.

But all these things were for the future. She was now sixteen and ahalf years of age. She had been at Hazlitt Chase for exactly sixmonths. She had not found any special niche in the school, but herteacher spoke fairly well of her, and she resolved to devote herself tothose accomplishments which might make her valuable by-and-by, and notfor a single instant to trouble her head about either moral or religioustraining.

"My place in this world is quite hard enough, and I cannot bother aboutany other," thought Penelope. "I must enjoy the present and get strong,and do right, because otherwise Mrs Hazlitt won't give me a characterof any use to me: and then I must get the best salary I can and savemoney for Brenda. At least, we could spend our holidays together."

These were Penelope's thoughts until that evening. But now all waschanged; for the daring idea had come into her head to ask MaryL'Estrange and Cara Burt to give her twenty pounds to send to hersister. They wanted her, Penelope, to take the part of Helen of Troy,and why should she not be rewarded for her pains?

"Their wishes are on no account because of me," thought the girl, "theyare all for themselves, because that silly Mary thinks she will lookwell as Jephtha's daughter, and Cara as Iphigenia. Neither of them willlook a bit well. There is only one striking-looking girl in the school,and that is Honora Beverley, and why she is not Helen is more than I canmake out. This will be a horrid piece of work, but where's the good ofsacrificing yourself for nothing? and poor old Brenda would be sopleased. I wonder if, whoever the present man is, he is really fond ofher? But whether that is the case or not, I am sure that she wants themoney, and she may as well have it. I was never up to much; but if Ican help Brenda, I will fulfil some sort of destiny, anyway."

These thoughts were quite sufficient to keep Penelope awake until theearly hours of the morning. Then she did drop asleep, and was notaroused until she heard Deborah's good-natured voice in her ears.

"Why--my dear Penelope,"--she said--"didn't you hear the first bell?You will be late for prayers, unless you are very quick indeed."

Up jumped Penelope out of bed. A minute later she had plunged her headand face into a cold bath, and in an incredibly short space of time shehad run downstairs and joined her companions just as they were troopinginto the centre hall for prayers.

This hall was a great feature of Hazlitt Chase. It was quite one of theoldest parts of the house. The girls' dormitories were quite neat andfresh with every modern convenience, but the hall must have stood in itspresent position for long centuries, and was the pride and delight ofMrs Hazlitt herself, and of all those girls who had any aesthetictastes.

Prayers were read as usual that morning, and immediately afterwards theroutine of the school began. The girls drifted away into their severalclasses. The special teachers who lived in the house performed theirduties. The music masters and drawing masters, who came from somelittle distance, arrived in due course. Morning school passed like aflash. Then came early dinner, and then that delightful time known as"recess." It was during that period that Cara and Mary had resolved toask Penelope Carlton to give her decision. Penelope knew perfectly wellthat they would approach her then. She had been, as she said, presentin the arbour on the previous night, and knew that Mrs Hazlitt had madeup her mind to give up the idea of Tennyson's "Dream of Fair Women," ifa suitable Helen was not to be found within twenty-four hours. It wasessential, therefore, for Penelope to declare her purpose during therecess.

She had by no means faltered in that purpose. During morning school shehad worked rather better than usual, had pleased her teacher--as indeedshe always did--by the correctness of her replies and the sort of quaintoriginality of her utterances.

She was a girl who by no means as yet had come to her full powers, butthese powers were stirring within her, dimly perhaps, perhapsunworthily. But, nevertheless, they were most assuredly there, and inthemselves they were of no mean order.

Penelope now walked slowly in the direction of the old Queen Anneparterre. This had not been touched since the days when that monarchheld possession of the throne. It was a three-cornered, lozenge-likepiece of ground, with the most lovely turf on it--that soft, very softgreen turf which can only come after the lapse of ages. Mrs Hazlittwas very proud of the Queen Anne parterre, and never allowed the girlsto walk on the turf, insisting on their keeping to the narrow gravelwalk which ran round it. There were high, red brick walls to theparterre on three sides, but the fourth was open and led away into a dimforest of trees of all sorts and descriptions, and these trees made theplace shady and comparatively cool, even on the hottest days.

Penelope, wearing a very shabby brown holland skirt and a white muslinblouse of at least three years of age, looked neither picturesque norinteresting as she strolled towards the parterre. She had not troubledherself to put on a hat. Her complexion was of the dull, fair sortwhich does not sunburn. She was destitute of any particle of colour;even her lips were pale; her eyes were of the lightest shade of blue;her eyelashes and eyebrows were also nearly white. As she walked alongnow, slightly hitching her shoulders, there came a whoop of delight fromthe younger children, and, amongst several others, Juliet L'Estrangeleaped towards her.

"Here you are! I am so glad! Why did you not come to us last night?We'd got such a glorious place to hide in--you couldn't possibly havefound us. What is the matter, Penelope? Does your head ache?"

"Penelope's head aches, I know it does," said Agnes, turning to hersmall companion as she spoke. "What is the matter, Penelope dear?"

"I am quite all right," replied Penelope; "but I can't talk to you justnow, Juliet, for I've something important to say to your sister Mary,and also to say to Cara Burt."

"But I thought you hated the older girls," said Juliet, puckering herpretty brows in distress. "You have always belonged to us, and that wasone reason why we loved you so much. You were always gay and bright andjolly with us. Why can't you play with us now?"

"Yes--why can't you?" asked Agnes. "It won't be a bit too hot to playhide-and-seek in the wood, and we have an hour and a half before we needgo back to horrid lessons."

"Yes--aren't the lessons detestable?" said Penelope. One of hergreatest powers amongst the younger girls was the manner in which shecould force them to dislike their lessons, judging that there would beno surer way of making them her friends than by pretending to dislikethe work they had got to do. She thus bred a spirit of mischief in theschool, which no one in the least suspected, not even the girls overwhom she reigned supreme.

She said a few words now to Juliet L'Estrange, and then walked on to theentrance of the wood, where she felt certain she would find Mary andCara waiting for her. She was right: they were there, and so also, toher surprise, were the other girls who were to take part in "A Dream ofFair Women."

It was arranged, after all, that only Helen of Troy, Iphigenia,Jephtha's daughter, Cleopatra, and Fair Rosamond were to act. QueenEleanor was not essential, she might come in or not, as the mistressdecided later on. But five principal actors there must be, and therestood four of them looking anxiously, full into Penelope Carlton's face.Annie Leicester was to take the part of Fair Rosamond. She was athoroughly unremarkable looking girl, but had a certain willowy graceabout her, and could put herself into grac

eful poses. The girl who wasto take the part of Cleopatra was dark--almost swarthy. Her name wasSusanna Salmi; and it needed but a glance to detect her Jewish origin.Her brow was very low; she had masses of thick, black hair, a largemouth, and a somewhat prominent chin. Her face, on the whole, wasstrong, and there were possibilities about her of future beauty, butthat would greatly depend on whether she grew tall enough, and whetherher buxom figure toned down to lines of beauty.

The four girls, such as they were, looked indeed in no way remarkable orsuited to their parts. But what will not judicious make-up andlimelight and due attention to artistic effect achieve? Mrs Hazlittwould not have despaired of the four, if only she had secured thecoveted fifth. If the girl she wished to be Helen of Troy

Daddy's Girl

Daddy's Girl A Very Naughty Girl

A Very Naughty Girl The Radio Detectives in the Jungle

The Radio Detectives in the Jungle A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls

A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls Mary Lee the Red Cross Girl

Mary Lee the Red Cross Girl Three Girls from School

Three Girls from School Maud Florence Nellie; or, Don't care!

Maud Florence Nellie; or, Don't care! David's Little Lad

David's Little Lad The Gold Kloof

The Gold Kloof Girls of the True Blue

Girls of the True Blue A London Baby: The Story of King Roy

A London Baby: The Story of King Roy A Girl in Ten Thousand

A Girl in Ten Thousand The Lady of the Forest: A Story for Girls

The Lady of the Forest: A Story for Girls The Palace Beautiful: A Story for Girls

The Palace Beautiful: A Story for Girls The Honorable Miss: A Story of an Old-Fashioned Town

The Honorable Miss: A Story of an Old-Fashioned Town Dumps - A Plain Girl

Dumps - A Plain Girl The Marines Have Landed

The Marines Have Landed Jill: A Flower Girl

Jill: A Flower Girl A Bevy of Girls

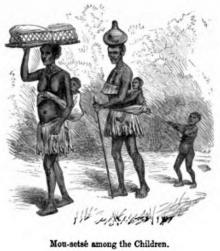

A Bevy of Girls Mou-Setsé: A Negro Hero; The Orphans' Pilgimage: A Story of Trust in God

Mou-Setsé: A Negro Hero; The Orphans' Pilgimage: A Story of Trust in God The Little School-Mothers

The Little School-Mothers Wild Heather

Wild Heather A Sweet Girl Graduate

A Sweet Girl Graduate The Girls of St. Wode's

The Girls of St. Wode's The Little Princess of Tower Hill

The Little Princess of Tower Hill The Time of Roses

The Time of Roses A World of Girls: The Story of a School

A World of Girls: The Story of a School A Plucky Girl

A Plucky Girl Turquoise and Ruby

Turquoise and Ruby Scamp and I: A Story of City By-Ways

Scamp and I: A Story of City By-Ways A Ring of Rubies

A Ring of Rubies The Squire's Little Girl

The Squire's Little Girl